The flash of yellowish green, black, and a bit of red as you disturb a Green Woodpecker up ahead, flying directly away from you in that classic, undulating flapping flight. Probing for ants, a favourite food, this one was on my front lawn, seen from indoors. The bill is remarkably large and dagger-like, and if I was an ant, I might feel quite intimidated.

I was aiming to capture, from an ant’s eye view, that intense look in the woodpecker’s eye as it concentrates on what can be had below.

The finished image continues the paper collage series.

After freshening up, chicken rice and spinach is served, followed by water melon

After freshening up, chicken rice and spinach is served, followed by water melon The same wall of heat hits me after dark as I step outside to make my way to our apartment. By lamplight, I see one or two moths, but dozens of large cockroaches

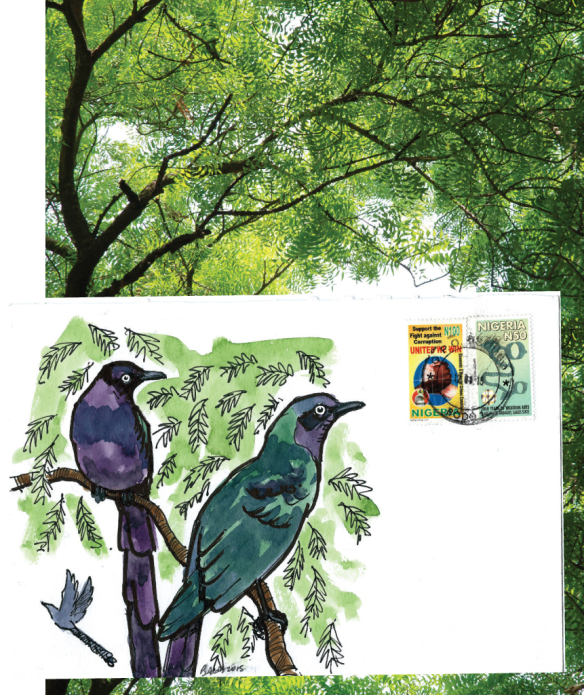

The same wall of heat hits me after dark as I step outside to make my way to our apartment. By lamplight, I see one or two moths, but dozens of large cockroaches I was familiar with these birds from ‘The Handbook of Foreign Birds’, where they were described as not for the novice, and could be quite aggressive towards weaker inmates

I was familiar with these birds from ‘The Handbook of Foreign Birds’, where they were described as not for the novice, and could be quite aggressive towards weaker inmates

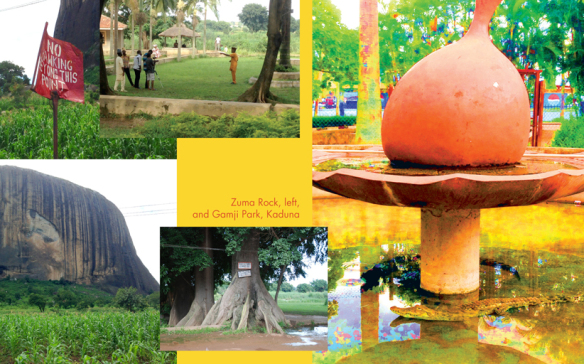

Toyin grew up in Kaduna and worked in the family hairdressing business in the town.

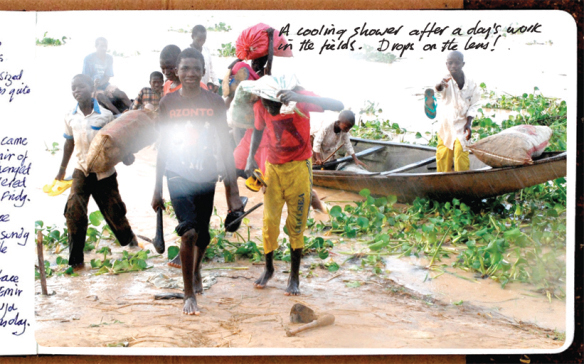

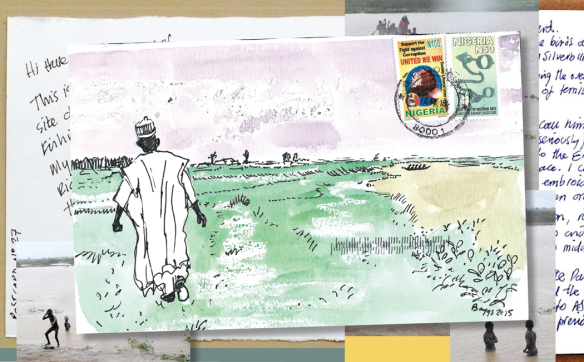

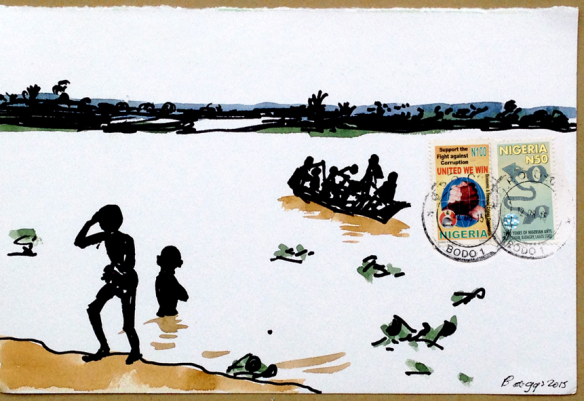

Toyin grew up in Kaduna and worked in the family hairdressing business in the town. Being adventurous and naive in equal measure I opt for a short walk along the lush riverbank which entails climbing through the broken chain link fence, which I manage relatively gracefully, and largely because I hear some exotic bird calls and hope to catch a glimpse. Sadly their identity remains a mystery. We did come across a fisherman however, who seemed quite happy to show us his catch inside the hollow calabash he was carrying above his head, and to show how he uses it as a float while he paddles to check his nets. Any fish are placed inside the calabash while he paddles off to the next net. ‘Are there crocodiles in the river?’ I ask, mentally assessing the risk the fisherman is taking ‘Yes’ said Sam, adding after a short pause ‘…though for a Nigerian, a crocodile is more an opportunity than a danger.’ I look down at my shoes, imagining what that might mean for Lowo’s handbag trade.

Being adventurous and naive in equal measure I opt for a short walk along the lush riverbank which entails climbing through the broken chain link fence, which I manage relatively gracefully, and largely because I hear some exotic bird calls and hope to catch a glimpse. Sadly their identity remains a mystery. We did come across a fisherman however, who seemed quite happy to show us his catch inside the hollow calabash he was carrying above his head, and to show how he uses it as a float while he paddles to check his nets. Any fish are placed inside the calabash while he paddles off to the next net. ‘Are there crocodiles in the river?’ I ask, mentally assessing the risk the fisherman is taking ‘Yes’ said Sam, adding after a short pause ‘…though for a Nigerian, a crocodile is more an opportunity than a danger.’ I look down at my shoes, imagining what that might mean for Lowo’s handbag trade.

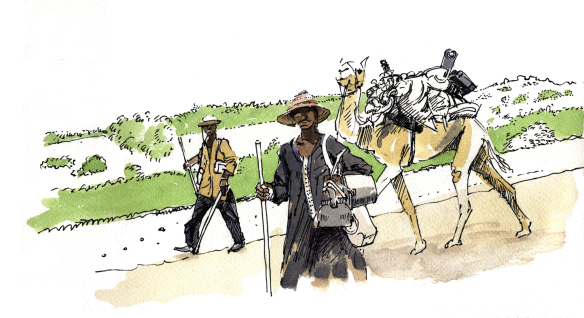

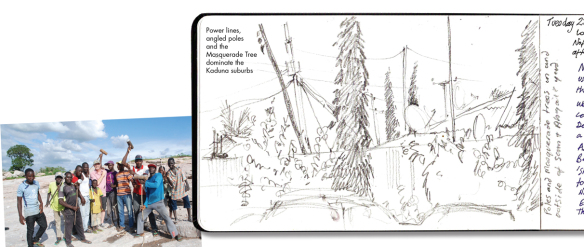

Sam and Abi are driving us back to Abuja this morning. We stop briefly for corn sticks roasted while you wait. Staying a few days with us until we leave for Birnin Kebbi turned out to be a happy decision, as we were able to spend a few more days in their good company while we figured out the best way of getting there, an internal flight or a nine hour drive.

Sam and Abi are driving us back to Abuja this morning. We stop briefly for corn sticks roasted while you wait. Staying a few days with us until we leave for Birnin Kebbi turned out to be a happy decision, as we were able to spend a few more days in their good company while we figured out the best way of getting there, an internal flight or a nine hour drive.