We are heading from Birnin Kebbi north-east to Argungu. It’s about 53 km. One perfect painterly composition after another whizzes past the car window. Rice and vegetables tended by people of all ages, groups of men sitting in the shade of trees, footpaths winding tantalisingly out of site into the green, the painterly rustic decay and distant rocky outcrops. The sun is already low and some heavy clouds are forming in the distance. Although it is getting towards the end of the day, there is still much activity on the streets, and trading goes on well after dark. Along the straight road, we pass some very fine looking horses tethered and being groomed and fed in the shade under the Neem trees.

We are intending to visit the Emir of Argungu in his palace, who will see us even at such short notice such are our connections. Set back off the road the walled compound has the look of a parade ground with buildings around the perimeter, some bedecked with flowering climbing plants. We come to a stop in the middle of the square. Groups of men sit around in the shade of the battered collonades and others stand in the open discussing the business of the day. Most are dressed Hausa style, one or two wear military combats and berets, and carry Kalashnikovs slung casually over their shoulders.

As we alight to stretch our legs, standing in the blinding sunshine bouncing straight upwards from the concrete, some staff approach our Hausa guide. He has a dark complexion and a weathered and lined face, highlighted by his elegant white kaftan and traditional hat. A brief discussion reveals the Emir unfortunately was summoned to Abuja and left yesterday, such is the nature of Nigerian politics.

Plan B comes into play as we now head back into town and make for the Argungu fishing village. The village is an extensive stretch of breeze block and grass roofed huts by the side of the Sokoto River, laid out like holiday camp chalets amongst generous, roomy avenues. One or two are occupied, but most are empty, and serve as home to many hundreds of hopefuls for the duration of the annual international fishing and sports festival, an important cultural event that has sadly been in decline in recent times. The apparent lack of maintenance of the village reflects this perfectly.

Sanusi drives as far as the terrain allows, almost to the river bank, where our guide encourages me to walk with him to the water’s edge. A boy is watering his donkey, and some other lads are washing fishing equipment in bright red plastic buckets. Some sand from the river is piled up lengthways along the shoreline, and knowing questions and answers in words are probably beyond us, I quietly assume the sand will be used for building the new fisherman’s huts set out nearby. I nod in approval albeit rather self consciously, which is taken as a signal to walk a little further on.

The scene is set for a hippo to surface with the pale mauve flowers of water hyacinth clinging to its ears – we’ve all seen the wildlife documentaries – but that isn’t going to happen. I am told there are crocodiles here, and in all the rivers we have seen so far, which fits nicely with my idea of the wild, dark continent. Standing here I have a rather different impression though, one I’ve not yet understood.

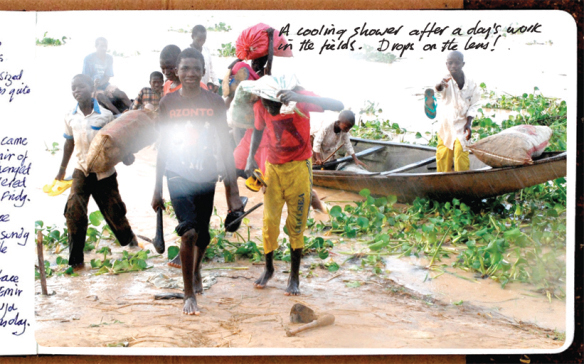

The water is a mix of sandy silt and a pale lavender grey reflection of the now cloudy sky. It starts to rain, but is refreshing and cooling. I spot the ferry boat coming across to our bank in the middle distance, and my guide recognises my interest and leads on along the rice paddies to meet it. We make it to the landing point before the boat arrives, the rain now more persistent. Two boys bathe in the water as the boat lands. The teenagers in the boat have finished working for the day, and throw their tools and slippers onto the sandy shore before disembarking, some carry sacks above their heads. The first few boys smile for the camera, and it completely slips my mind to wipe the raindrops off the lens, but no matter. By now rain soaked, I try and absorb the enormity of the landscape, the hard living. The moment is heavy and laden with paradox.

The walk back to the pick up is quite a long one, and I feel confident enough in my

paddy walking skills to take a slightly different route than my guide as the terrain is drier.

I’m not sure why this feels strangely risqué and later put it down to the adventure.

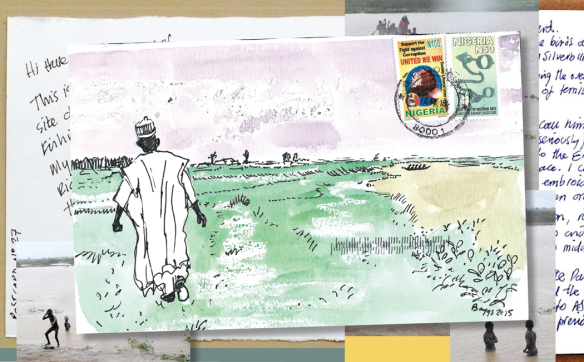

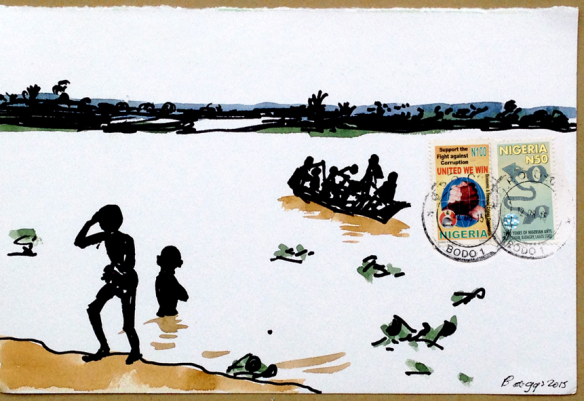

Once we are underway the rain quickly stops and the drive back to Birnin Kebbi sees the sun give the trees and grasses and crops a backlit golden glow before setting behind more birds on wires. Later I make two postcards of the scene along the river, one of my guide leading me across the rice paddies to meet the ferryboat, and of the boys watching the

boat come in.